Sacagawea.com ®

Sacagawea.com ® is a Registered TrademarkMotion Picture, Television, Video, and Media Productions

|

|

|

|

Sacagawea was kidnapped in 1800, which would have made her about 13 years old, by the Hidatsa tribe, and some sourses believe, was kept as a slave. Other sources say that she became part of the tribe. Sacagawea was either purchased by, or won through gambling (depending on the source), a French-Canadian fur trader named Toussaint Charbonneau, and became his wife. Sources differ on when this took place; some say that Sacagawea was 16 at the time, other sources say that she was 15 or 14. It should be noted that Toussaint Charbonneau was already married to another Shoshone woman at the time he married Sacagawea.

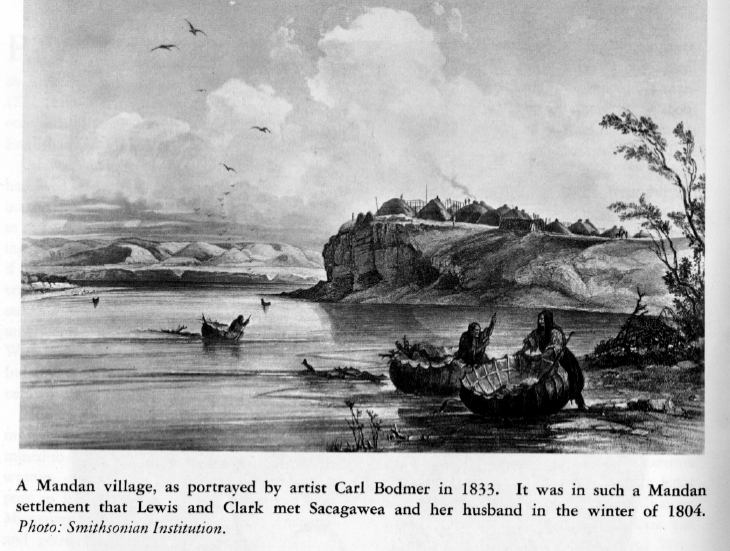

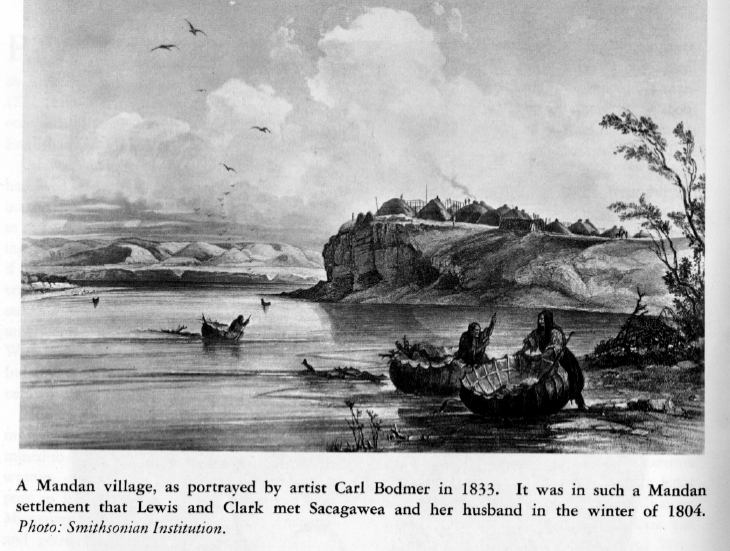

During the winter of 1804 and 1805, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, and the Corps of Discovery arrived. They were looking for a translator to translate the Hidatsa language for help with trading and when they talked to Charbonneau, they discovered that his wife Sacagawea also spoke Shoshone, they hired Charbonneau as interpreter, with Sacagawea as an accompanying unpaid interpreter, with their expedition from the Northern Great Plains to the Pacific Ocean. Sacagawea was pregnant at the time. On February 11, 1805, Sacagawea gave birth to her son, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau while they were staying with the Corps of Discovery at Fort Mandan. When other Native American Tribes would see the group, they assumed that the Corps of Discovery was friendly, since there usually wasn't a war party with a mother and her baby. According to many sources, William Clark nicknamed him Pomp, or Pompy, or Pompey. However, some sources, including a few Native American sources say that he was named Pomp by Sacagawea, which meant first born.

Sacagawea helped the Corps of Discovery with local navigation, horse trading, translating, keeping peace with other tribes, finding edible food, and was the one who rescued Clark's journals, along with other valuable items, from the Missouri river when Charbonneau capsized their boat. Sacagawea made the entire trip with her child. She later had a daughter named Lisette. In December of 1812, she died of diphtheria. which at the time was known as putrid fever. However, many Native American resources state that she died on a reservation in Wyoming on April 9, 1884. According to the U.S. Mint, more statues, streams, lakes, landmarks, parks, songs, ballads, and poems honor Sacagawea than any other woman in American history.

Sacagawea became a member of the Corps of Discovery because her husband, Toussaint Charbonneau, was asked to join as an interpreter. She was a young woman, only 16 years old in 1804, with a newborn infant, when the group set out for the unknown West. She helped the party by digging roots and other types of foods, showing the men how to make leather clothes and moccasins, and saving important papers from a capsized canoe. Sacagawea was a member of the Shoshoni tribe who had been captured by Hidatsa Indians when she was about 12, and taken to the Hidatsa Villages many hundreds of miles from her home on the upper Missouri River. She later became the wife Charbonneau.

Slave Or Adopted?

A misconception arose about Sacagawea’s status in the Hidatsa tribe over the years, to the point where she is generally regarded in history texts and works of fiction to have been a slave. This is not true – in fact, there was no place in the Hidatsa culture for slavery. Ethnologist Alfred W. Bowers, in his classic study of the Hidatsas, put it best: "Adoption of children of alien tribes, when the parents were unable to care for them or they had been abandoned by their parents while trading at the Hidatsa villages, was of common occurrence. . . . These children when adopted frequently assumed the position of a child who had died, while the kinship bonds with the blood relatives were never broken. They could return to their own tribe when grown and nothing would have been done to prevent it. . . .

"Another group adopted into the villages was composed of prisoners, comprising women, small children, and even babies, when it was possible to bring them back safely without danger from counterattack. A woman sometimes would ask a brother leaving for war to bring her a child, to replace one that had recently died, instead of a horse. Women prisoners were taken as wives and the children captured with them lived in their mother's household. Motherless children were adopted and cared for by other households. If a girl was approaching marriageable age, she was usually taken into a household without formal adoption and assisted the women of the household until she could be married to some young man who would assist in the hunting. The most illustrious prisoner to become a member of the tribe was Bird Woman, the Shoshoni guide for Lewis and Clark in 1805-1806. By residence at Awatixa village, she became a member of the Itisuku clan."

Returning Home

Ironically, as Sacagawea went westward with Lewis and Clark, she got closer and closer to her homeland. In the Three Forks area she began to recognize many landmarks. Meriwether Lewis, with a small party of his men, made the first contacts with the Shoshoni, eventually meeting Chief Camehawait and trying to bargain for horses and guides to get over the Rocky Mountains. Sacagawea stayed behind with her husband, baby, and William Clark, with the bulk of the expedition's soldiers and supplies. Lewis waited for several days for Clark to arrive, and when he was late, brought Shoshoni suspicion upon himself and his motives. It was with the arrival of Clark that Camehawait began to believe Lewis' story. And then, in a scene that no Hollywood fiction writer could ever get away with, the Indian woman with the baby standing in the background recognized the chief as her long-lost brother! After the affecting reunion between brother and sister, Sacagawea was instrumental in translating for Lewis and Clark and acquiring the needed horses. Instead of electing to stay with her people, Sacagawea decided to continue with the expedition to the Pacific. Even on the return journey, Sacagawea did not remain with her people in Montana and Idaho, but stayed with her husband and returned to the Mandan Villages in North Dakota.

"Sa-ca-ga-wee-uh" Many people ask questions about the spelling of the name Sacagawea. Sacagawea with a "G" is the way the name was most frequently written by the explorers themselves, with the pronunciation specified in their original journals as including a hard G sound in the third syllable (or sa-ca'-ga-wee-uh).

To The Coast And Back

The Lewis and Clark expedition traveled a total of nearly 8,000 miles round trip from St. Louis to the Pacific Coast and back. This was because their route was not directly across the continent, but followed the twists and turns of the Missouri and later the Columbia river systems. Sacagawea traveled an estimated 4,356 of those miles, according to mileage figures for the dates she accompanied the expedition, taken from the original journals.

A Short But Very Interesting Life

According to one version of the Sacagawea story, she died at about 25 years of age in 1812 at Fort Manuel (a fur trading post named for Manuel Lisa), along the Missouri River near the border of modern-day South and North Dakota (Corson County, South Dakota). A clerk at the fort named John C. Luttig kept a journal, and on December 20, 1812 noted that "This evening the wife of Charbonneau, a Snake squaw, died of putrid fever. She was a good and the best woman in the fort, aged about twenty-five years. She left a fine infant girl." Some have suggested that Charbonneau had two Snake (Shoshoni) wives, Sacagawea and Otter Woman. Could it have been Otter Woman who died in 1812, and not Sacagawea? Unfortunately, Luttig's journal provides no clues. However, he says that the woman who died "was a good and the best woman in the fort," which certainly meshes with Clark's comment that Sacagawea was "of mild and gentle disposition." Charbonneau was not at the fort when his wife died, and had still not returned in March 1813 when a raiding party of British and Indians (the War of 1812 was raging) burned the fort to the ground. Luttig took the baby girl, named Lizette, and a ten year old boy named Toussaint (probably the son of Charbonneau and Otter Woman), to St. Louis, and was legally made the guardian of the children in Orphan's Court. By August 1813, however, Luttig's name was crossed out in the records of the court and the name of William Clark substituted. Luttig may have been ill, for he died in 1815. Or perhaps Clark felt he could do a better job of providing for the children. There is some evidence that Clark did not at first believe the woman who died and was buried in an unmarked grave at Fort Manuel to be Sacagawea. By 1825, however, Clark's annotated list of Corps of Discovery members listed her as being dead.

The best historical evidence states that Sacagawea died December 20, 1812 at Fort Manuel. Sacagawea lived a short but very interesting life. She packed an incredible amount of adventure into 25 short years, and got to see the wonders of the North American continent as few men or women have before or after her time.

Sacagawea - Captive, Indian Interpreter, Great American Legend

Sacagawea.com ®

admin@sacagawea.com

Copyright 1999-2007, Sacagawea.com ®, All Right Reserved.

Please note: We are not historians with regards to Sacajawea (Sacajawea, Sakakawea), Native American Indian History or the Lewis and Clark Expedition. We are providing this information as a public service, which is based on numerous and sometimes conflicting resources. We strongly recommend that if you are looking for more information on Sacagawea, that you search the Internet and the numerous books that have been written about Sacagawea and the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The sites and links on this site are provided for information purposes only; Sacagawea . com ® is not connected with them in any way.